- Music services

- Audio services

- Forensic Musicology

- CV & Credits

- Contact

- Lessons

- Music Copyright Checker - Compare Melodies, Rhythms, & More

- The FAV Corpus

- Music Theory For Producers

- Music Theory Placement Exams

- Copyright Cheat Sheet: Finding Substantially Similar Songs

- All I Want For Christmas Is (Sue) You: A Forensic Musicologist On The Mariah Carey Case

- Mexico City WhatsApp Groups

- Music Retreat

|

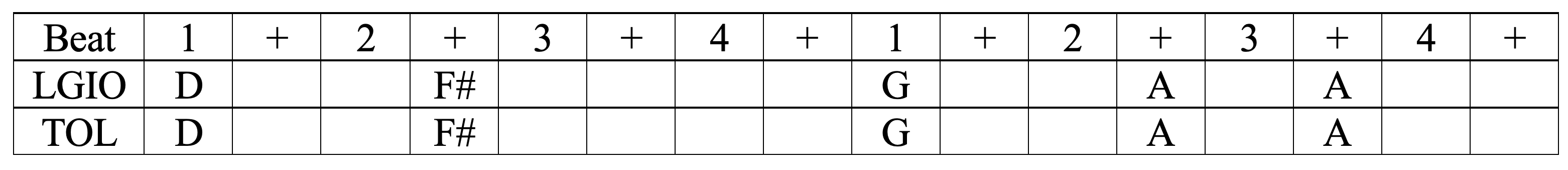

This article was originally published in Law360's Expert Analysis column: link For attorneys working music copyright infringement cases, the question of substantial similarity often depends on experts who conduct a systematic comparison of similarity and difference between two musical passages. There is no better example than Griffin v. Ed Sheeran, the recent and high-profile case of Marvin Gaye's "Let's Get It On" against Ed Sheeran's "Thinking Out Loud," where the experts, called forensic musicologists, on either side duked it out in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York over the songs' basslines, vocal melodies and chord progressions.[1] But too frequently, legal practitioners are in the dark when it comes to understanding the basic musical elements, and knowing which ones are actually important for perceiving similarity or difference. For instance, did you know that many well-known elements like key, genre and tempo don't actually matter for whether two melodies sound similar or not? The goal of this article is to provide a useful overview or cheat sheet for attorneys of which musical elements do and do not, when altered, create the sense of a new or distinct composition. Throughout the article, I'll be using Griffin v. Sheeran as a case study, giving you the tools to avoid some common mistakes made by attorneys, judges and juries alike, and helping you get ahead of your peers in winning music copyright cases. In this article, I will show you the elements that can actually be changed a great deal without affecting a tune's identity or recognizability, and then discuss the true heavy lifters — even a moderate change to these elements, and you may have yourself a new song.[2] I. The Song Remains the Same: Elements That Don't Usually Affect Similarity In this section, I present musical elements that are not usually important for musical similarity. In other words, if these elements are modified, they will not sound like a new or different song. Fundamentally, the song remains the same. Tempo Tempo is the speed or pace of music. When we talk about a fast or slow performance of a song, we are talking about tempo. Changing the tempo does not change the core identity of a song, because all the notes and their relationships are still there. As an example, consider two renditions of "Happy Birthday," one at a slow pace and one at a fast pace: While changing the tempo of a song can affect its emotions, energy level and even its genre, we can all agree that "Happy Birthday" performed slow or fast is still "Happy Birthday."[3] You are now already armed to consider one of the claims regarding "Let's Get It On" and "Thinking Out Loud." The plaintiff's experts remarked that the two songs have very similar tempos.[4] But tempo is generally unimportant for melodic identity. Therefore, we should place little stock in claims of tempo. Key The key of a melody essentially refers to its tonal center or home. You can take a song and systematically shift all of its notes up or down, changing its key. Many people assume it's a big deal to change the key of a song, but it actually doesn't change anything structural about the song. As a demonstration, you can listen to "Happy Birthday" in two different keys: A major, then E-flat major: Even though they look very different on the score, they sound like the same melody. This is because all the important relationships — pitch, rhythm and contour, which I discuss below — are preserved. The melody is the same, it's just played a little lower or higher. Just as a person on the first, second or third floor of a building is still the same person, a song in C major, D major, E major, etc. is still the same song. So, the fact that "Let's Get It On" and "Thinking Out Loud" are in two different keys — E-flat major and D major — may sound like a point in favor of the defendant, but it actually means very little.[5] Instrumentation "Instrumentation" refers to the instruments used to perform or record a song. Playing a song on a flute versus a violin, or on a trumpet followed by a harp, would clearly still be the same song: Though the tone color — what musicologists call "timbre" — is very different between the renditions, the same tune can be heard. "Let's Get It On" and "Thinking Out Loud" both have bass, drums, guitar and piano, among other instruments. But while similar instrumentation can help to put two songs in the same genre, which may fuel a claim of access, the shared instrumentation in itself has nothing to do with a shared melodic structure. Dynamics "Dynamics" refer to louder or quieter notes in a song. We can turn up or down the volume, and it still remains the same song. Similarly, a quiet or loud performance of a song is still the same song. In the following example, you can hear two versions of "Happy Birthday" with exact opposite dynamics. What is loud in Version A is soft in Version B, and vice versa. Though they sound odd, both versions are still recognizably the same song: Style Style or genre depends on a number of factors, such as what instruments are used, what types of chords and rhythms are used and so forth. But a change of style in itself does not really create a different song. This is the whole idea of cover songs: When Alien Ant Farm gives their hard-rock rendition of Michael Jackson's funk and dance record "Smooth Criminal," the genre and energy has totally changed. But it is still recognizably the same song, rather than a new composition. This is because the vocal melody, lyrics, harmonies and song structure all remain the same in most cover songs. Just as a painter can portray an object in any number of visual styles — cubist, impressionist, realist, etc. — a musician can present the same song in different musical styles, such as rock, jazz, reggae, etc. Harmony Harmony is the use of two or more notes, called "chords", sounding at the same time. Also known as a song's "changes" or "chord progression", harmony is determined by the bassline and chords in the production — rarely by the vocal melody, which is what grabs our ear. Therefore, because of the primacy of melody, a song can usually be reharmonized — keeping the same melody but changing its bass and chords — and still remain recognizable. Listen to "Happy Birthday" with its regular, expected harmonies, followed by a totally reharmonized version: The reharmonized example is pretty wild, but we can still recognize the song because its melody line has not changed. While most people can recognize a song by its melody alone, very few could identify it by its chords alone. Besides, myriad songs reuse the same chord progressions. In the "Thinking Out Loud" case, a lot of the argument between competing musicologists was dedicated to harmony: The defendant's experts argued that the chord progressions in the two songs are fundamentally different, while the plaintiff's experts argued that they are fundamentally the same.[6] But now that we've seen that harmony isn't even that important for recognizing a tune, perhaps that debate doesn't matter that much. So what does matter? The pitches, rhythms and contour of the notes, to which we now turn. II. Beating to a Different Drum: The Elements That Usually Are Important for Similarity The elements in this section are the heavy lifters of musical similarity — change them, and you usually have yourself a new song. Rhythm "Rhythm" refers to the durations of events in music. It is the aspect that can be expressed by a percussion instrument, or by clapping or tapping. Listen to "Happy Birthday" with its rhythms removed: If you strip away the rhythm from a melody, you rob it of much of its character and recognizability. One study found that even tunes as well-known as "Happy Birthday" or the national anthem are only recognized by half of listeners when presented in a "rhythm-less" format.[7] Much of the "Thinking Out Loud" case hinged on the songs' basslines. The plaintiff's experts argued that the basic rhythm, as well as the pitches, of both basslines were identical:[8] This is a pretty strong similarity, unlikely to happen by chance alone. And we know that rhythm is critical for perceived similarity. So this was a major point in favor of the plaintiff. Crucially, however, it's a reduction of the basslines, conveniently omitting several notes that differ between the two basslines. Pitch "Pitch" refers to what we think of as "the notes". In standard Western music there are 12 of them: A, B, C, etc. The choice of pitches in a melody is very important for its identity and recognition. For instance, take a listen to this version of the "Happy Birthday" melody with a few notes changed, colored in green: Unless someone told you this was derived from "Happy Birthday," you probably wouldn't figure it out. In fact, when researchers kept the original rhythm of famous tunes such as "Happy Birthday" and the national anthem, but used totally different pitches, only 8% of listeners could still recognize the songs:[9] When the researchers removed pitch entirely, creating "pitch-less" versions that only had rhythm, that number dropped to 6%: Therefore, it's no surprise that pitch is one of the most-discussed elements in music copyright cases: Pitch is a true heavy lifter for melodic similarity. In the "Thinking Out Loud" case, one of the plaintiff's experts argued that both songs' vocal melodies include the same identical 4-pitch and 5- pitch runs.[10] This can easily seem like a smoking gun: "Wow, look at all those identical notes in a row!" However, their rhythms are totally different. Without going into too much detail, they enter on different beats of the bar and use different durations. Pitch similarity alone is rarely enough for a strong musicological argument of true similarity. Contour "Contour" refers to the shape or direction of a melody. When we describe a melody as going up, down or any other shape, we are describing its contour. If you keep the pitch and rhythm the same, but you change the contour, a melody can become completely unrecognizable. How do I mean? You keep the same notes, but move them to different octaves.[11] This is best demonstrated by an example. Can you identify this popular tune? If you correctly identified it, congratulations. If not, don't worry — the vast majority of people can't recognize it. The example comes from a classic study in which the contour of "Yankee Doodle" was modified — recognition of the tune plummeted from 100% to only 12% of listeners.[12] And all we have done is moved the notes up or down to other octaves. We've kept the exact same pitches and rhythms. Simply by changing the contour of the melody, we have transformed it into something unrecognizable to the ear. Contour played a role in "Thinking Out Loud": Although the defendant's expert conceded that both songs' basslines begin with D-F#, he argued that their contour is different. One bassline goes up, from D to a high F# above, while the other goes down, from D to a low F# below.[13] III. Conclusion Although long the domain of experts, today's attorney needs to have a basic understanding of the generally important and unimportant elements of musical similarity perception. This understanding will aid you in intelligently assessing an expert's claims, and effectively persuading juries and judges. Nowhere was this more relevant than the recent "Thinking Out Loud" case, where much confusion could have been avoided by a more informed understanding by all parties of some basic musical points, as I outlined in this article. I hope this article is a useful musicology primer for attorneys tackling music copyright cases that clarifies some long-standing myths and misconceptions, such as the mistaken idea that songs in different keys or tempos are fundamentally different. I have shown how a change in aspects like tempo, key, instrumentation, dynamics, style and harmony usually has surprisingly little impact on the song's true identity. I also presented the heavy lifters of pitch, rhythm and contour: Remember, change any of these aspects enough, and you have a different composition.[14] The question then becomes, how much difference is enough? The answer to that question, I leave in the hands of my legal betters. [1] Griffin v. Sheeran, 1:17-cv-05221, (S.D.N.Y.)

[2] A disclaimer: I am not making a claim about the legal protectability of musical elements from a copyright perspective. After all, I am a music expert, not a legal expert. I am just describing the important elements of music that matter for two songs to sound similar or different. [3] Richard M. Warren, Daniel A. Gardner, Bradley S. Brubaker & James A. Bashford. Melodic and Nonmelodic Sequences of Tones: Effects of Duration on Perception, 8(3) MUSIC PERCEPTION 277 (1991). [4] See Griffin v. Sheeran, 1:17-cv-05221, (S.D.N.Y.), Document 67-6, Filed 07/27/18, Page 3. [5] Nor did Defendant's expert claim that the difference of keys was particularly significant. (See Griffin v. Sheeran, 1:17-cv-05221, (S.D.N.Y.), Document 67-3, Filed 07/27/18, Page 4). Also, note that, as with similar tempo, similar key can bolster a claim of copying insofar as it is easier to copy something when it is already in the same key or tempo. But similar key in itself has no bearing on a melody's identity - a melody remains the same regardless of what key it is played in. [6] Specifically, it came down to a disagreement about whether the I6 and iii chords are equivalent or not. [7] Sylvie Hébert & Isabelle Peretz. Recognition of Music in Long-Term Memory: Are Melodic and Temporal Patterns Equal Partners?, 25 MEMORY & COGNITION 518 (1997). [8] See Griffin v. Sheeran, 1:17-cv-05221, (S.D.N.Y.), Document 67-6, Filed 07/27/18, Page 5. [9] Sylvie Hébert & Isabelle Peretz. Recognition of Music in Long-Term Memory: Are Melodic and Temporal Patterns Equal Partners?, 25 MEMORY & COGNITION 518 (1997). [10] See Structured Asset Sales, LLC v. Sheeran, 1:20-cv-04329, (S.D.N.Y.), Document 1, Filed 06/08/20, Pages 33-34, Examples 5a and 5b. [11] An octave is an interval of 12 semitones. For example, from "middle C" on the piano to the C above it is an octave, as is any C# to the next C# above or below it, etc. The note names from octave to octave are the same. They just sound lower or higher depending on which octave they occur in. [12] Diana Deutsch. Octave Generalization and Tune Recognition, 11 PERCEPTION & PSYCHOPHYSICS 411 (1972). [13] See Griffin v. Sheeran, 1:17-cv-05221, (S.D.N.Y.), Document 67-3, Filed 07/27/18, Pages 18-20. I have transposed both to D major for ease of comparison; the actual notes in question are Eb-G in "Let's Get It On" vs. D-F# in "Thinking Out Loud". This is a rather nuanced situation, as contour is indeed critical to melodic similarity, but in the case of basslines, it actually matters extremely little...it is very common for basslines to use large leaps and changes of octave. As the bassline's role is generally to provide the chord roots, the ear is not typically concerned with a bassline's specific contour. Therefore, in my opinion the difference of the bass motion up a third in one song and down a sixth in the other song, is almost entirely trivial. [14] I reiterate that my presentation of some elements as generally unimportant for musical similarity (Section 2, "The song remains the same") and other elements as generally important for musical similarity (Section 3, "Beating to a different drum") is not to be conflated with a claim about the protectability of said elements from a copyright perspective.

0 Comments

|